The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) — which requires state courts to make active efforts to protect Native children and keep Native families together — is currently at risk of being gutted by the Supreme Court in Brackeen v. Haaland. Congress passed ICWA in 1978 to address the nationwide crisis of state child welfare agencies tearing Native children from their families and placing them in non-Native homes, in an attempt to force Native children to assimilate and adopt white cultural norms.

Fighting to Keep Native Families Together

Less than half of Native Americans live in a state with an ICWA law on the books. Email your state representatives and urge them to pass or update their state ICWAs to protect Native children and recognize placement preferences created by tribal governments.

Being removed from their homes and families and disconnected from culture, tradition, and identity profoundly harms Native children and has lasting, lifelong impacts. We spoke to two Native people who shared their stories about the impacts of child removal, why ICWA is important, and why Native families have a right to stay together.

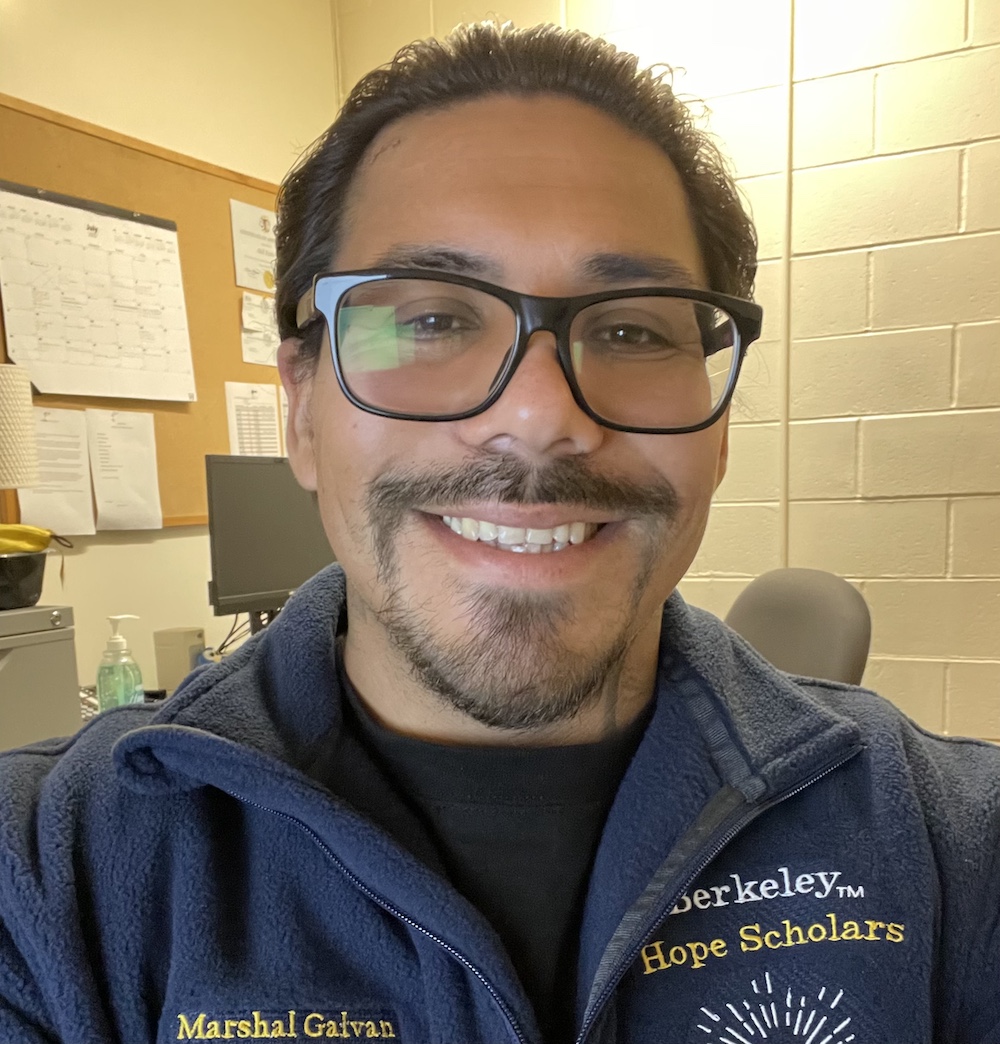

Marshal Galvan Jr., Little Shell Chippewa

Marshal Galvan Jr.

Credit: Marshal Galvan Jr.

When I was a child, I remember going to powwows. I remember seeing Native people. I remember being happy in these spaces with my family, and in my eyes and in my sisters’ eyes, my parents could do no wrong. But for whatever reason, the child welfare system decided that my parents weren’t good parents, and they decided to take that right of parenthood away from them.

When my sisters and I were placed in the child welfare system, we were initially placed together, but we got split up and placed into different homes over the years. They said we were bad kids and no one would take all of us on because we were a handful to deal with. Looking back now, we were just kids who were traumatized. We were kids that just wanted to go back to the safety of our parents.

My first placement was in a foster home with a white family. I didn’t learn about Catholicism or Christianity until I entered foster care. As I went through the system, I started landing in different homes with different cultures and languages being spoken, in different cities, schools, and neighborhoods. Everything constantly changed, and it constantly reinforced an identity crisis in my life.

By the time I was a teenager, I was gravitating towards anything and everything that I felt was going to connect me to something — whether it was the gang, drugs, or alcohol. It gave me a false sense of pride, ego, and meaning to life. I was putting myself in risky situations so that I could feel a part of my community. In my young adult life, things started shifting for me. I started getting incarcerated. I turned 18 and became homeless immediately. My addiction took a turn for the worse. Suicidal ideation and hopelessness started setting in. All along, I was grappling with my identity and just really seeking to know my roots.

Marshal Galvan Jr. as a child.

Credit: Marshal Galvan Jr.

In 1997, when my parents lost their rights, there was no support and there certainly wasn’t any communication between our tribe and our family or the courts. At the time, the social workers and courts weren’t making active efforts to help our family bridge those gaps. My family’s tribe, Little Shell, wasn’t federally recognized until 2019. Because of that lack of federal recognition, my family was glossed over and wasn’t protected under ICWA.

My tribe allowed me enrollment membership into the tribe on August 23, 2022, but I’ve never lived in Montana and I don’t know the practices of my tribe. I acknowledge that. But through my enrollment, I am learning and rediscovering things about my tribe, and it has given me the ability to share that with my family. I started to reconnect with my family, and my enrollment is helping 16 other family members reconnect with the tribe, including my dad who wants to relearn his roots. I think it’s a beautiful thing.

It’s been a journey to unlearn, decolonize myself, and decolonize my mind. It’s an ongoing process, and I still have to do a lot of healing. To this day, as a tribal person, I still am facing an identity crisis. But no one should ever feel like they’re not Native enough, or enough, period.

It’s been a journey to unlearn, decolonize myself, and decolonize my mind.

Now, my passion is helping people that have similar stories to mine. Currently, I’m a counselor and work with youth in the Berkeley area. I would like social workers that are working in the child welfare system to continue to educate themselves on their own biases, because we’re hurting families. We’re keeping kids away from their parents and families when they don’t need to be.

The Indian Child Welfare Act is important because it keeps people like myself connected to our cultural roots, our family lineage, and our birthright. Not only does it respect tribal sovereignty, it also gives Native kids an opportunity to choose whether or not they want to embark on a journey that’s a birthright. To have the opportunity to have community, to be able to have folks that I can look around at and say, these are my people. That’s the most important thing — family, community, and cultural roots.

Mondae Vanderwalker, Rosebud Sioux Tribe

Mondae Vanderwalker

Credit: Mondae Vanderwalker

It took me three and a half years of jumping through hoops and dealing with wrongdoings from the Department of Social Services (DSS) and the court system to adopt my two nephews.

My oldest nephew was taken away from my brother when he was around 3 years old. He was put in the system, and I called the local DSS office and told them that I wanted to get custody and adopt my nephew. The DSS representative told me “No, we’re not going any further or moving forward with this case,” just because they heard some hearsay about me. But they never looked into the allegations. I asked DSS, “Well, how come you won’t do a background investigation or whatever you have to do so that I can get my nephew? He’s an important part of my life.” And they just kept saying, no, we’re done here.

I had no money to fight this, and didn’t know what to do. A few years later, my younger nephew was born, and he was also taken away from my brother when he was just a few months old. After he was taken, a woman from a different DSS office contacted me and asked, “Would you be interested in taking him?” and I said, “Yes,” in a heartbeat. I was waiting for that phone call for many years.

DSS had me and my husband go through a program to get a foster parent certificate to start the process of adopting our nephews. Once we were finalized for the adoption process, DSS finally let us go see my nephews at their foster family’s home. We had to drive from Sioux Falls two and a half hours away each weekend to go see them. But on our third visit, the foster family tried to keep us from visiting. I thought the agreement was that we were working on getting these children placed back with us, but the foster family kept trying to block our visits. DSS representatives warned me: “You’re going to have a battle on your hands — the foster family wants to adopt these children.”

I kept thinking, “I need to do something about this, because I’m going to lose my nephews.” I talked to someone I knew on our tribal council and then to our tribal president and told them what was going on. I told them I was afraid I was going to lose my nephews, because we were coming down to the wire, and the foster family got a lawyer to try to keep our nephews from us. They even tried to argue that my oldest nephew was not an enrolled tribal member, which would have made him ineligible for protection under ICWA. If that had happened, the foster family would have been able to adopt him right away. But thankfully, my brother did fill out tribal enrollment papers for my older nephew years ago — it turned out that DSS just had never turned them into the court.

Our tribal president ended up hiring a lawyer to help me fight for my nephews and we went to court. ICWA ended up saving us. If one of my nephews was not a Native American child, a non-Native person would have been able to adopt them without any question, and I would have lost them. But after a three and a half year battle, I was finally able to legally adopt my nephews under ICWA.

My two nephews are now 8 and 4 years old. Once we were reunited, I felt relieved, like a lot of pressure was taken off my shoulders. I was happy that the fight was finally over and that we could finally just live our lives. I want to help more people to understand ICWA and to tell them to not give up. If I didn’t talk to somebody and try to get help, they would have been gone. But I fought and fought and never gave up. It makes you think — how many more people, how many children who are sacred to Native American people, do you think we lost like that, in this system?

My nephews love me for what I’ve done because now they know a lot about powwows, everything to do with the tribe, and our ancestors. Before, they didn’t know any of that. They didn’t know what a powwow was. They didn’t know what fry bread was, or what Indian tacos were. But they do now. Now, they can have a better understanding of their culture and where they came from.

If ICWA was not put in place, I would have lost my nephews. The ICWA guidelines are important, but the state has to follow them. When my nephews were first placed in the system, my tribe was supposed to be involved from the get go, but they weren’t. Under ICWA, it was the responsibility of a DSS worker to call our family and tribe to let them know that these children were placed in a foster home with non-Native American families, but that didn’t happen. Our tribe needs to know that these children are in this system. And they should have known about it a long time ago.

If ICWA was not put in place, I would have lost my nephews.

When government workers don’t follow the ICWA guidelines, it hurts our people by allowing our children to be adopted out to other families and away from their tribe. ICWA is there to protect us, and DSS needs to do more to help these Native American children be placed back with their families.

ICWA helps us keep our children with their families like they should be. Our children need to stay with us, and we need to keep our families together.